Difference Between a Keyhole and a Door

Uniting the Best of Culture, Commerce & Science for America's Creative Future

Renowned philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer observed that everyone mistakenly interprets the limits of their own field of vision as the limits of the world. This tendency to mistake our narrow perspectives for the full picture is not just a philosophical observation—it’s a recurring theme in scientific discovery.

Consider the 1978 discovery of Pluto’s largest moon, Charon. For years, astronomers discarded elongated images of Pluto, assuming they were photographic distortions. It wasn’t until James W. Christy recognized a pattern in those discarded images that Charon was revealed. What was once considered an error became a breakthrough.

Narrow views can also obscure discovery when we examine how business leaders are trained to think about creativity. Everyone wants to believe there is an easy, quick fix to cure their company’s creativity pains. The media obliges and often reports neuroscience findings as a simple answer to a complex challenge. But if innovation were simple, every business would be a creative powerhouse.

While leaders may be personally interested in increasing their individual creativity, the more important question for their organization is how to turn their teams' creative potential into scalable innovation.

A Keyhole View of Creativity

An interesting new study by Kutsche et al. (2025), published in JAMA Network Open, maps neuroimaging findings of certain aspects of creativity and brain disease onto a common brain circuit. This past week, media outlets started pushing out the findings with a multicolored brain image and a headline: Brain Circuit for Creativity Identified.

Many of my LinkedIn followers sent it to me, asking for thoughts. I read the study a couple of times and talked to scientist colleagues who know more than I do about the brain. Below, I’ve put together a few top-of-mind reflections to prime the pump for further dialogue.

The core finding suggests that creativity is connected to turning off self-censorship, a process linked to negative functional connectivity in the right frontal pole of the brain.

This finding is not inconsistent with what some of the top creativity researchers outside of neuroscience have noted:

Sternberg’s Investment Theory of Creativity suggests that creativity thrives when individuals “buy low” on unconventional ideas and champion them until they gain acceptance (Sternberg & Lubart, 1995).

Boden’s Three Types of Creativity (combinational, exploratory, and transformational) show that breakthrough ideas depend on a combination of flexible thinking and rule-breaking, which are influenced by the brain’s ability to suppress self-censorship (Boden, 2004).

Reiter-Palmon’s Work on Team Creativity demonstrates that psychological safety is necessary for innovation, allowing people to take risks without fear of failure (Reiter-Palmon & Illies, 2004).

On the one hand, the new study confirms what we already know—creativity is not just a personality trait but a measurable and modifiable brain function. But if we take this finding as the entire picture rather than a keyhole glimpse, we risk missing the deeper complexity of how creativity operates in business, innovation, and culture.

More Than Just a Creativity “Brake”

The study’s central claim is that reducing activity in the right frontal pole—the brain area associated with self-censorship—may enhance certain aspects of creativity. The logic here is that creativity flourishes when we silence our inner critic, allowing ideas to flow freely.

As I said, that makes sense at first. I’ve got a long history as part of the theatre community. And, in improvisation, “yes and” is improv’s most important rule. It’s a team-level arts modality of the same idea.

But here’s where I pause.

Beyond self-censorship, the right frontal pole area also contributes to high-level decision-making, goal-directed behavior, and reward processing, playing a role in evaluating ideas, managing social interactions, and sustaining motivation under uncertainty. These functions are essential for translating team-level creativity into valuable innovations within organizations.

Businesses can’t just focus on generating more raw ideas if they want to build successful innovation-driven teams. They need teams that can:

Balance novelty with strategic evaluation.

Sustain motivation through the long, messy process of innovation.

Collaborate effectively in creative problem-solving.

Organizational performance depends on three factors: cognition, motivation, and collaboration. The right frontal pole plays a key role in high-level decision-making, goal-directed behavior, and reward processing, which support both cognition and motivation. While it does not directly drive collaboration, it is part of the Executive Control Network (ECN), which supports sustained attention, complex problem-solving, and working memory— all essential for applied creativity in organizations.

So, before we get excited by a headline promising a magic answer to optimizing brain-based creativity, its a good idea to always be aware of the unintended consequences that may arise in different cultural contexts

A Disease-Based View of Creativity Has Limits for Business

When it comes to research, it's important to remember who conducts and funds it.

Take, for example, creativity research in healthcare vs. non-healthcare fields. The scientific cultures of different fields shape their focus and methodologies. In healthcare and medicine, creativity research prioritizes medical problem-solving, diagnostics, and treatment innovations. In contrast, non-healthcare fields—such as business—tend to emphasize market disruption, interdisciplinary problem-solving, team creativity, and user experience, allowing for different approaches to risk, experimentation, and implementation. Both areas are outcome-driven, but how creativity is studied and applied varies based on each field's goals, constraints, and cultural contexts.

These differences are not about the quality of research but rather the institutional and cultural norms that define how creativity is framed, studied, and applied. A decade ago, WHO and The Lancet identified the neglect of cultural contexts in health research as a major barrier to achieving the highest attainable global health standard. They highlighted that creativity in medicine often overlooks alternative innovation models. This underscores that creativity research—whether in healthcare or beyond—is always a cultural product shaped by disciplinary priorities, funding structures, and societal values.

The Kutsche study and many others are based on a disease-based understanding of creativity. They often draw conclusions by assessing people with brain lesions or neurodegenerative disorders. This approach is valuable to us all, but it differs from studying how high-functioning teams operationalize creativity in business.

Granted, Kutsche and colleagues aren’t attempting to define a business use case from their work. They use a disease-based approach to understand what happens when the brain’s regulatory functions break down. On its own terms, this is important work. As with many things in life, the problem comes with translating it into different contexts.

Herein lies the challenge for business leaders: Sometimes, even the most fascinating neuroscience findings won’t easily translate into innovation ecosystem design as a standalone idea.

For example, if leaders were to assume that reducing self-censorship was the most important action for innovation, they might mistakenly believe that a priority should be to remove structure and let ideas run wild. But successful innovators aren’t just idea generators. They know how to refine, validate, and execute those ideas in a way that creates real impact.

In other words, creativity without strategic discipline doesn’t fuel business growth. It fuels noise.

Importantly, here, I want to stress that it’s not science but the media stories and headlines about science that present our greatest challenges.

Humans Are, By Nature, Explorers

Throughout the history of American enterprise, three maxims of exploration and discovery have fueled our cultural and economic growth: Minds conceive. Hearts believe. Teams achieve.

Today, however, 80% of executives report they cannot innovate quickly enough. Why? Organizations continue to overlook and misunderstand the creative skill sets essential for success. The World Economic Forum’s Future of Jobs Report 2025 reinforces this, identifying these cognitive, emotional, and social skills as essential problem-solving skills for thriving in an AI-driven world.

We know what to do, but our siloes between disciplines and sectors are holding us back.

Fear remains the top barrier to innovation (85% of practitioners report it), yet fewer than 11% of companies address it.

Innovation grief, skills gaps, and attention deficits erode return on investment.

AI-driven industries are booming but often lack emotional and cultural intelligence, likely leading to reduced product-market fit, team burnout, and stalled innovation cycles.

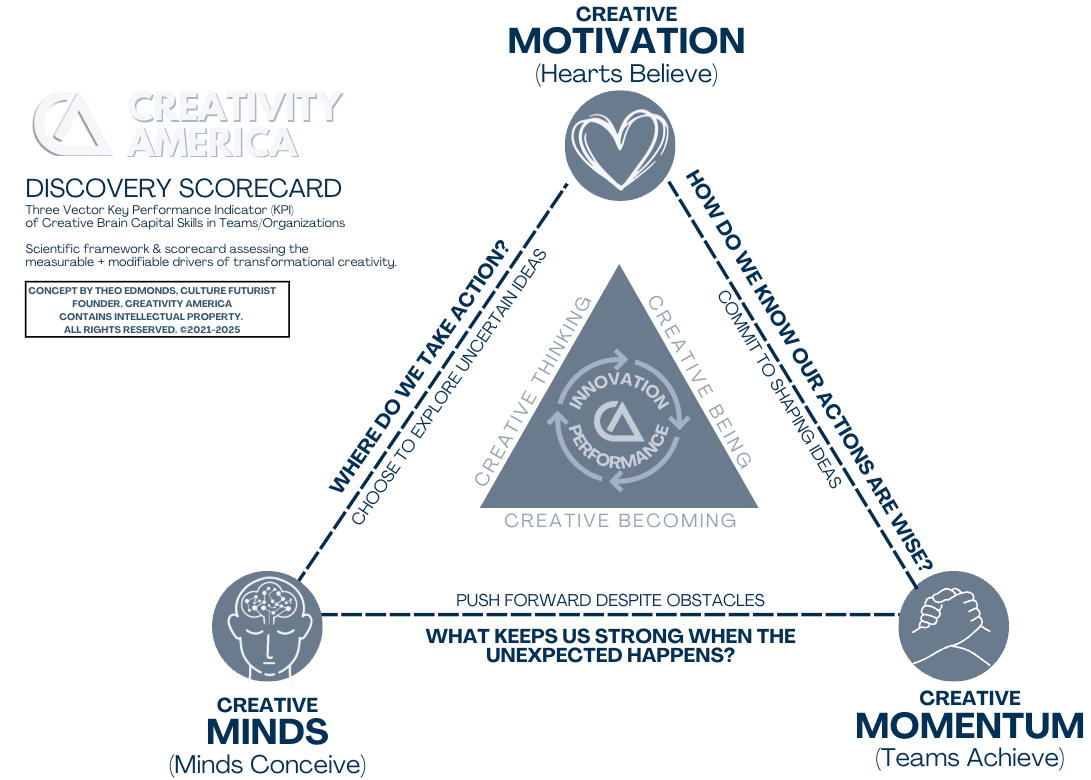

That’s why Creativity America developed a Discovery Scorecard to assess Creative Brain Capital in teams and companies. This performance framework combines neuroscience, industrial psychology, and the arts to measure, align, and enhance the creative skill sets that drive group innovation.

Unlike traditional assessments focused on individual traits, Creative Brain Capital is the foundation for developing full-spectrum creativity into a key performance indicator (KPI) for organizational innovation.

By offering a structured yet flexible method, the framework unites the best of culture, commerce, and brain science to strengthen creative resilience in AI-driven economies. If innovation is a priority, companies actively cultivating creativity's cognitive, emotional, and social elements will perform better than those who don’t.

Here’s how to think about the three skill vectors of Creative Brain Capital.

MINDS CONCEIVE: Follow Steve Job’s Advice and Train People to “Think Different”

Implement structured creativity training that teaches employees how to shift between divergent (idea generation) and convergent (idea evaluation) thinking (Beaty et al., 2016).

Cognitive flexibility exercises can encourage lateral thinking and reduce rigid problem-solving approaches (Benedek et al., 2018).

Invest in R&D teams that blend analytical and creative skills, ensuring they are trained in critical and expansive thinking.

HEARTS BELIEVE: Activate “Discovery Mode”

In high-performance teams, motivation is not just about productivity—it’s about emotional states that enable breakthrough thinking and persistence during uncertainty. Creativity America has identified four key Discovery Mode amplifiers that support Creative Brain Capital:

Wonder: The balance between awe and curiosity, fueling innovation.

Trust: The balance between hope and belonging, ensuring psychological safety.

Freedom: The balance between compassion and courage, enabling risk-taking.

Joy: The balance between working with purpose and pleasure, sustaining motivation.

TEAMS ACHIEVE: Design for Courageous Collaboration

Encourage risk-taking and reduce fear of judgment in team meetings (Edmondson, 1999).

Create environments where unconventional thinking is tested and rewarded rather than immediately dismissed (Amabile, 1996).

Use collaborative problem-solving frameworks that allow teams to build on each other’s ideas before critique begins (Reiter-Palmon & Illies, 2004).

Final Thought

Research can give us powerful insights into how creativity works in the brain, but it doesn’t automatically translate into business-ready innovation strategies. If we take only the “keyhole” view of a complex process like creativity, we could unintentionally encourage more creative output without a system for refining and applying it. And that’s not what the world’s most innovative companies do.

They balance freedom with discipline. They encourage bold thinking but within structures that allow for strategic execution. They train co-creative teams, not just creative individuals. That’s the real lesson here for business leaders.

The synergy between technology and neuroscience has long been a wonderful driving force behind interdisciplinary human progress. It should continue to be supported and invested in at the highest levels. This is why I am so proud to be part of efforts like the Brain Capital Alliance and the Business Collaborative for Brain Health.

There, too, is something more that seems equally important right now. As AI takes on a growing role in creativity and problem-solving, businesses have a rare opportunity unique to this moment in human history. Namely, to hardwire the processes and tools that unlock human creative potential of teams into our innovation technologies. Not as an afterthought, but as a feature. This is the best way to mitigate risk and ensure that our deep and unprecedented technological investments lead to transformative outcomes.

Buckminster Fuller is an architect, systems theorist, and futurist whose work has always inspired me. His work in design, sustainability, and human-centered innovation—most famously the geodesic dome—advanced a vision of technology serving humanity with his "Spaceship Earth" concept promoting shared responsibility and resource efficiency.

“None of us, including me, ever do great things,” he says. “But we can all do small things, with great love, and together we can do something wonderful.”

I love this because it reinforces that innovation isn’t about isolated genius or individual breakthroughs—it’s about how we work together, uniting the best of arts, science, and business into something far greater than the sum of its parts.

That’s why I want us to get creativity right, not only to understand it in the brain but also to unlock its full power across American enterprise—culture AND commerce.

My Other Places, Other Frames

Culture Futurist Substack: Business, Innovation & Future of Work

Poetry Substack: Culture Kudzu: Poetry for Entrepreneurs -

Professional: Creativity America

Personal: Culture Futurist

Theo Edmonds, Culture Futurist® & Founder, Creativity America | Bridging Creative Industries and Brain Science with Future of Work & Wondervation®

©2021-2025 Theo Edmonds | All Rights Reserved. This article contains proprietary intellectual property. Reproduction, distribution, or adaptation, in whole or in part, requires accurate attribution. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of any affiliated organization or institution.